In recent years Morrissey has taken to reissuing his back-catalogue albums. The repackaging of a couple of mid-1990s efforts has seen him radically alter cover art, reorder track listings (in some cases leaving originally included songs off altogether) and adding single b-sides and previously unreleased curios. All very nice for the completist, of course - but a bit of a pedantic course of action from a man purported to be happy enough in his own skin in recent years to let the past lay as it fell.

There's no getting away from the fact that 1997's Maladjusted - perfectly perfunctory but a tad uninspired - was, at that time, an exasperating let-down. It is far too late for the perverted act of dropping a couple of songs almost fifteen years hence to change general perception.

Similarly, reordering the track listing of 1995's Southpaw Grammar and adding a couple of outtakes could never disguise the fact that it had to do the hardest job of any album Morrissey has ever - or will ever - release.

It had to bear the weight of following 1994's Vauxhall And I.

V&I is such a self-contained record that it lives almost entirely outside of Morrissey's entire canon. It's not as commercial as any other Morrissey record, for a start, but it really doesn't sound like any other Morrissey record, and it doesn't read like any other Morrissey record. It's not that it's a musically odd album - far from it - but it has a uniqueness of sonic tone, emotional tone, a maturity and self-analysis that none of his other albums could ever hold a candle to.

It's my belief that it is the only album he has released which IS Morrissey. That's Morrissey the man, not Morrissey the cartoon.

There's no getting away from the fact that 1997's Maladjusted - perfectly perfunctory but a tad uninspired - was, at that time, an exasperating let-down. It is far too late for the perverted act of dropping a couple of songs almost fifteen years hence to change general perception.

Similarly, reordering the track listing of 1995's Southpaw Grammar and adding a couple of outtakes could never disguise the fact that it had to do the hardest job of any album Morrissey has ever - or will ever - release.

It had to bear the weight of following 1994's Vauxhall And I.

V&I is such a self-contained record that it lives almost entirely outside of Morrissey's entire canon. It's not as commercial as any other Morrissey record, for a start, but it really doesn't sound like any other Morrissey record, and it doesn't read like any other Morrissey record. It's not that it's a musically odd album - far from it - but it has a uniqueness of sonic tone, emotional tone, a maturity and self-analysis that none of his other albums could ever hold a candle to.

It's my belief that it is the only album he has released which IS Morrissey. That's Morrissey the man, not Morrissey the cartoon.

It was born in a time when Morrissey was still preoccupied with bruisers, boxers, black-and-white movies, books, the ephemera of a passed England... which, of course, had gotten him into trouble with the popular music press, and set up the psychological watershed of what followed...

V&I came from a time before the smash-and-grab of Britpop had been breach-born, when England was still under Conservative rule. You can feel the tiredness, the greyness, the dissatisfaction, the atrophy, the complete dulling of the senses and the squeezing of the skull - and the romantic strive to make one last stand against the numbness of having lived through Thatcher's socially, psychologically, diminishing rule. It was rumoured - a rumour occasionally furthered by the man himself - that this was to be Morrissey's final album.

V&I came from a time before the smash-and-grab of Britpop had been breach-born, when England was still under Conservative rule. You can feel the tiredness, the greyness, the dissatisfaction, the atrophy, the complete dulling of the senses and the squeezing of the skull - and the romantic strive to make one last stand against the numbness of having lived through Thatcher's socially, psychologically, diminishing rule. It was rumoured - a rumour occasionally furthered by the man himself - that this was to be Morrissey's final album.

At the relevant point in time, Morrissey was living in Camden. The title of the album is a direct reference to Bruce Robinson's Withnail And I, the story of two down-at-heel London actors barely co-existing there in an inter-dependant and mutually self-destructive blur of vague psychoses and neuroses, alcohol, drugs, squalor and unfulfilled promise in the late 1960s: "Indeed we are drifting in the arena of the unwell"...

It has hinted that Morrissey was engaged in a similar kind of cloistered, intense and consuming relationship as that portrayed in the film, and here romanticised it onto vinyl. Perhaps not explicitly - perhaps it is only there around the edges, a mood, an oblique reference here and there, a provocative nod. But maybe this album was Morrissey finally coming out with the truth - or the truth as he chose to tell it, filtered through that entirely charming but peculiar self-regard. V&I almost lays Morrissey's private life utterly bare without actually saying the thing that dare not speak its name, taunting you into using that word, then roundly chastising you for having the temerity to even think it, to even presume a single thing.

Beautifully crafted songs seem like intensely private diary entries, portraying - and in some cases betraying - deep-held feelings and thoughts. On this record, which seems to have been written entirely for himself and is all the better for it, Morrissey doesn't shy away from the murk of depression, hypocrisy, the ache of lust, love, sorrow, satire, hate, anger, ageing, regret, humour.

It's all here, lyrically - in Morrissey's own strange way of course - with producer Steve Lillywhite's instinctive and painterly ambience perfectly creating a tangible and complementary mood and tension which has often been absent from the more visceral production of other Morrissey records. From the off, we're let know that this time, this once, this was something different.

Opener Now My Heart Is Full begins with a wash of melancholic guitars fashioning previously uncharted sonic territory, exploring deeper textures and moods. I'm reluctant to use the word "filmic", but a film is what the first few seconds evoke, and the rest of the album is entirely elevated to the status of the cinematic.

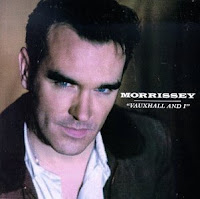

Blue-eyed, sensible-quiffed, geometric cheek-boned Morrissey stares out from the cover in a beautifully lit portrait which strongly evokes 1950s cinema matinee idols, before delivering a prosaic Coronation Street killer opening line in deep and rich velvet tones: "There's gonna be some trouble..."

Blurry-eyed late-night gin-soaked trudges through rained-on brickwork back-streets are precisely located in a London that exists, really, only in Morrissey's mind, all slate-grey skies, lamplight reflecting in puddles, 1960s suits, tattoos and slicked-back hair - and the danger of a knife. References to Graham Greene's Brighton Rock add further layers to the romance of crime, the romance of grime, the threat and the thrill. The passing of crime and all of its times.

The song shares a moment of mood with the rush to danger of the bond forged in the mask-theft scene in Breakfast At Tiffany's, as if now fully committed, with no turning back. It is perhaps no accident that Morrissey recorded that film's Moon River as an addendum b-side to one of Vauxhall's singles.

No other Morrissey song has sounded so enormously melancholic as Now My Heart Is Full. Scarcely believable that he should be redeemed and completed. Really? Or, of course, is he nodding back to the Northernisms of Weatherfield again, with "full" meaning sorrowful..? There's gonna be some trouble...

Spring-Heeled Jim begins with a bass throb and distorted guitar wail that expand on the darkness of those London alleyways, suggesting the danger of a killer, a Jack The Ripper, even. But it turns out to be an observational, mournfully wry, take on the diminishing process of getting older, the demise of everything that self-defines a chancer, a wide-boy, a womaniser. Time passes, chances fade - all fades as self slows. The passing of time and all of its crimes.

Two minute thrash Billy Budd - title taken from Herman Melville - vaguely recalls The Smiths' London, and seems to mischievously throw references to Johnny Marr into the legend: "Twelve years on since I took up with you...". But who really knows? The fact it's followed by Hold On To Your Friends does, though, add further credence to this theory.

A contemplative ballad that somehow made it out as a single, heavily acoustic Hold On is beautiful. "There are more than enough to fight and oppose, so why waste good time fighting the people you like?". Earnest and open, surprisingly generous, utterly gracious and graceful.

With its arresting couplet "...beware, I bear more grudges than lonely High Court judges", the album's lead-off single The More You Ignore Me The Closer I Get is an exercise in wilful pursuance. Great title and - despite anything Elvis Costello might tell you about Morrissey songs being no more than the sum of their title - a classic song, focused around an attractive guitar motif and lovely vocal melody.

It's about as close as we've ever got to Morrissey acknowledging this album's existence in recent years. It has occasionally cropped up in his set list, and on a surfeit of hits albums. In many ways, being pretty straightforward it is probably the only song from this album that could even be well-served by a live set-up - potential inclusion on the Glastonbury setlist, then.

Why Don't You Find Out For Yourself - the grass is not always greener - is a sturdy riposte to those who, from the safety of sitting in an armchair behind a copy of the NME, have criticised Morrissey's career choices. Paradoxically, to an agreeably radio-friendly acoustic backing, it dissects and displays the hypocrisies, cynicisms and manipulations of the music business in vague but colourful detail, taking wistful and well-aimed potshots at the faceless, nameless, men in suits.

Used To Be A Sweet Boy could just about be the most straightforward song Morrissey has ever written. It puzzles over the "something" that "went wrong" between the "distant land" of childhood, with its "blazer and tie and a bright healthy smile", and the man now. It's a sepia-toned snapshot of a regretful man gazing at a sideboard photograph of himself as a young boy, holding his Dad's hand. Lush, romantic and yearning. No, I just have something in my eye.

I Am Hated For Loving, Lifeguard Sleeping, Girl Drowning and The Lazy Sunbathers deal with lazy misconception, apathy, emotional and actual, and selfishness. Gentle, mournful, slightly Smithsish, none fully prepare us for the tempest to come.

Speedway bitterly addresses the proceedings in a court-room and could therefore be seen as sage and angry comment on Morrissey's own experiences therein.

Following the opening seconds of jaw-dropping direct address to the judge - "When you slam down the hammer, do you see it in your heart?" - the broken plea for human understanding outside of the strict technical confines of the legal process is utterly carved up by a few seconds of silence, then the loud scream of a chainsaw. It's wilfully disturbing.

But the song could also be Morrissey's most explicit Oscar Wilde moment - no longer content to merely reference, this is authorship, art, biography. Morrissey actually inhabits the writer to express the tumult within during the infamous trial which led to his eventual downfall: "You won't rest until this loving mouth is shut, good and proper" / "You won't sleep until the hearse that becomes me, finally has me"... Stirring, trembling, defiant.

During the final couple of minutes the song builds progressively intensely, until release - but not closure - is delivered by a brief and sonically stark drum tumble signifying the final slam of the judge's gavel.

It's been an intense and perfect 39 minutes. Perfect.

A couple of times in a lifetime along comes something that cuts much deeper, darker, more defiant. Something you can disappear into, something that demands of you. There are many reputedly classic albums which are so precisely crafted and drawing-board designed that they fall woefully short of displaying any real insight or personality - or anything substantial of what it means to be alive. Many albums are exercises in creating terrific listens but conclude with you knowing nothing more about yourself or anything or anyone else at the other end, leaving you with merely the aftertaste of a fleetingly enjoyable moment.

Perhaps, in the end, that is all music was ever meant to be..? Perhaps we shouldn't actually be looking for deeper displays or analysis of the human condition from music..? I'm really not, as a rule, but I love them when they come, and I do keep my fingers crossed and sleep with half of one eye open. Tick-tock.

It has hinted that Morrissey was engaged in a similar kind of cloistered, intense and consuming relationship as that portrayed in the film, and here romanticised it onto vinyl. Perhaps not explicitly - perhaps it is only there around the edges, a mood, an oblique reference here and there, a provocative nod. But maybe this album was Morrissey finally coming out with the truth - or the truth as he chose to tell it, filtered through that entirely charming but peculiar self-regard. V&I almost lays Morrissey's private life utterly bare without actually saying the thing that dare not speak its name, taunting you into using that word, then roundly chastising you for having the temerity to even think it, to even presume a single thing.

Beautifully crafted songs seem like intensely private diary entries, portraying - and in some cases betraying - deep-held feelings and thoughts. On this record, which seems to have been written entirely for himself and is all the better for it, Morrissey doesn't shy away from the murk of depression, hypocrisy, the ache of lust, love, sorrow, satire, hate, anger, ageing, regret, humour.

It's all here, lyrically - in Morrissey's own strange way of course - with producer Steve Lillywhite's instinctive and painterly ambience perfectly creating a tangible and complementary mood and tension which has often been absent from the more visceral production of other Morrissey records. From the off, we're let know that this time, this once, this was something different.

Opener Now My Heart Is Full begins with a wash of melancholic guitars fashioning previously uncharted sonic territory, exploring deeper textures and moods. I'm reluctant to use the word "filmic", but a film is what the first few seconds evoke, and the rest of the album is entirely elevated to the status of the cinematic.

Blue-eyed, sensible-quiffed, geometric cheek-boned Morrissey stares out from the cover in a beautifully lit portrait which strongly evokes 1950s cinema matinee idols, before delivering a prosaic Coronation Street killer opening line in deep and rich velvet tones: "There's gonna be some trouble..."

Blurry-eyed late-night gin-soaked trudges through rained-on brickwork back-streets are precisely located in a London that exists, really, only in Morrissey's mind, all slate-grey skies, lamplight reflecting in puddles, 1960s suits, tattoos and slicked-back hair - and the danger of a knife. References to Graham Greene's Brighton Rock add further layers to the romance of crime, the romance of grime, the threat and the thrill. The passing of crime and all of its times.

The song shares a moment of mood with the rush to danger of the bond forged in the mask-theft scene in Breakfast At Tiffany's, as if now fully committed, with no turning back. It is perhaps no accident that Morrissey recorded that film's Moon River as an addendum b-side to one of Vauxhall's singles.

No other Morrissey song has sounded so enormously melancholic as Now My Heart Is Full. Scarcely believable that he should be redeemed and completed. Really? Or, of course, is he nodding back to the Northernisms of Weatherfield again, with "full" meaning sorrowful..? There's gonna be some trouble...

Spring-Heeled Jim begins with a bass throb and distorted guitar wail that expand on the darkness of those London alleyways, suggesting the danger of a killer, a Jack The Ripper, even. But it turns out to be an observational, mournfully wry, take on the diminishing process of getting older, the demise of everything that self-defines a chancer, a wide-boy, a womaniser. Time passes, chances fade - all fades as self slows. The passing of time and all of its crimes.

Two minute thrash Billy Budd - title taken from Herman Melville - vaguely recalls The Smiths' London, and seems to mischievously throw references to Johnny Marr into the legend: "Twelve years on since I took up with you...". But who really knows? The fact it's followed by Hold On To Your Friends does, though, add further credence to this theory.

A contemplative ballad that somehow made it out as a single, heavily acoustic Hold On is beautiful. "There are more than enough to fight and oppose, so why waste good time fighting the people you like?". Earnest and open, surprisingly generous, utterly gracious and graceful.

With its arresting couplet "...beware, I bear more grudges than lonely High Court judges", the album's lead-off single The More You Ignore Me The Closer I Get is an exercise in wilful pursuance. Great title and - despite anything Elvis Costello might tell you about Morrissey songs being no more than the sum of their title - a classic song, focused around an attractive guitar motif and lovely vocal melody.

It's about as close as we've ever got to Morrissey acknowledging this album's existence in recent years. It has occasionally cropped up in his set list, and on a surfeit of hits albums. In many ways, being pretty straightforward it is probably the only song from this album that could even be well-served by a live set-up - potential inclusion on the Glastonbury setlist, then.

Why Don't You Find Out For Yourself - the grass is not always greener - is a sturdy riposte to those who, from the safety of sitting in an armchair behind a copy of the NME, have criticised Morrissey's career choices. Paradoxically, to an agreeably radio-friendly acoustic backing, it dissects and displays the hypocrisies, cynicisms and manipulations of the music business in vague but colourful detail, taking wistful and well-aimed potshots at the faceless, nameless, men in suits.

Used To Be A Sweet Boy could just about be the most straightforward song Morrissey has ever written. It puzzles over the "something" that "went wrong" between the "distant land" of childhood, with its "blazer and tie and a bright healthy smile", and the man now. It's a sepia-toned snapshot of a regretful man gazing at a sideboard photograph of himself as a young boy, holding his Dad's hand. Lush, romantic and yearning. No, I just have something in my eye.

I Am Hated For Loving, Lifeguard Sleeping, Girl Drowning and The Lazy Sunbathers deal with lazy misconception, apathy, emotional and actual, and selfishness. Gentle, mournful, slightly Smithsish, none fully prepare us for the tempest to come.

Speedway bitterly addresses the proceedings in a court-room and could therefore be seen as sage and angry comment on Morrissey's own experiences therein.

Following the opening seconds of jaw-dropping direct address to the judge - "When you slam down the hammer, do you see it in your heart?" - the broken plea for human understanding outside of the strict technical confines of the legal process is utterly carved up by a few seconds of silence, then the loud scream of a chainsaw. It's wilfully disturbing.

But the song could also be Morrissey's most explicit Oscar Wilde moment - no longer content to merely reference, this is authorship, art, biography. Morrissey actually inhabits the writer to express the tumult within during the infamous trial which led to his eventual downfall: "You won't rest until this loving mouth is shut, good and proper" / "You won't sleep until the hearse that becomes me, finally has me"... Stirring, trembling, defiant.

During the final couple of minutes the song builds progressively intensely, until release - but not closure - is delivered by a brief and sonically stark drum tumble signifying the final slam of the judge's gavel.

It's been an intense and perfect 39 minutes. Perfect.

A couple of times in a lifetime along comes something that cuts much deeper, darker, more defiant. Something you can disappear into, something that demands of you. There are many reputedly classic albums which are so precisely crafted and drawing-board designed that they fall woefully short of displaying any real insight or personality - or anything substantial of what it means to be alive. Many albums are exercises in creating terrific listens but conclude with you knowing nothing more about yourself or anything or anyone else at the other end, leaving you with merely the aftertaste of a fleetingly enjoyable moment.

Perhaps, in the end, that is all music was ever meant to be..? Perhaps we shouldn't actually be looking for deeper displays or analysis of the human condition from music..? I'm really not, as a rule, but I love them when they come, and I do keep my fingers crossed and sleep with half of one eye open. Tick-tock.

Vauxhall And I is Morrissey's masterpiece. A neat and uncompromisingly brilliantly penned book - but no easy read. In the examining of battle scars and in the laying to rest of old ghosts, it is optimistic, but opens up fresh wounds, fists fly, glass shatters. It's occasionally difficult, but ultimately life-enhancing, poetic and telling - an absolutely essential listen if you have even the slightest interest in circumnavigating the lazy myth of the quiff and the quip and getting straight to the bottom of Morrissey.

So far, it appears to be the one exception from those devious, truculent and unreliable efforts to repackage and rewrite history. It is to be hoped that Morrissey realises that to give or take a further inch of it would be to demean his work and himself. Listen and marvel, you will never hear the like again.

No comments:

Post a Comment